|

I am truly blessed to be a farmer. There is not a day that goes by that I would rather be doing anything else. It is without doubt, one of the most vibrant, dynamic, meaningful vocations that I can think of.

I wake up in the morning to the chattering of corellas outside my bedroom window, perched in swaying gumtrees. My horse whinnies for me to feed her before I have my own breakfast, and by mid-morning I’m usually bumping along a track with my mum to go check the fences or clean out a sheep trough. During the heat of the day I am indoors at my computer. I have just finished my PhD – on how to recycle and revalue agricultural by-products to improve soil fertility and capture nutrients within local farming systems – and I am now writing a book on food systems. In the afternoons I often have teleconferences, where I connect with people working on climate change and food security. These conversations are focused on harnessing the energy that swells in people who are determined to change the current trajectory. They share my enthusiasm for making meaningful difference. At sunset I walk our dogs down to the dam, where they run, bark and splash in the evening light. We often take binoculars to the water’s edge to check out the birdlife – these last few weeks we’ve spotted white-faced herons, rainbow bee-eaters and black-fronted dotterels. Kangaroos nonchalantly hop down for a drink amongst the evening’s goings-on, and swallows skim the water’s surface for insects as the sun dips below the horizon. Rural Australia is a place you can easily fall in love with. She is beautiful and calming. She is also extremely fragile. My love for this place is why when I see her in pain, I feel that pain. I experience the drought, heatwaves and dust-storms with her and I see the toll it takes on the place I call home. Climate change is having severe impacts on my home, and like farmers around the world, I am concerned about how we will produce food as conditions worsen. If you’ve ever stood before an approaching dust-storm, you will know what I mean when I describe it as a formidable dark beast crawling along the landscape. Bellowing a low grumble as it makes its way across vast stretches within minutes, unfolding to the heavens and engulfing everything in its way. It’s a sight we farmers in far western New South Wales see often during drought. A powerful reminder of one’s insignificance in the face of Mother Nature – and simultaneously our great impact upon her. Humans have been greedy, asking too much of our common home. Chain-sawing forests, sucking rivers dry, consuming more than is able to be replenished. We have degraded our life-support system, and we are now paying the price for that behaviour. The dust-storms that I witness on my family’s farm highlight just how vulnerable we are. In this region that I call home, it is projected to become hotter, drier and that we’ll experience more frequent and intense droughts and heatwaves. So what does the future hold for the semi-arid inland Australia? How do farmers like me produce food to feed a rapidly growing global population in a climate troubled world? Our future rests in our hands today. I am one of the founding Directors of an Australian organisation called Farmers for Climate Action. It is a group that gives me hope and energy in a time when it is easy to feel overwhelmed and lost. Farmers for Climate Action is a movement of farmers, agricultural leaders and rural Australians working to ensure farmers are a key part of the solution to climate change. It is a farmer-led organisation that specialises in climate action, and we work across the agricultural and climate sectors to manage risks and find opportunities to adapt to, and mitigate, climate change. Our theory of change is simple. We believe that if we organise farmers, graziers and agriculturalists, to lead climate solutions on-farm and advocate together, we can influence our sector and the government to implement climate policies that reduce pollution and benefit rural communities. Our work is supported by four strategic pillars; · Farmer education and training:We are working to ensure farmers have the tools they need to remain profitable and sustainable long-term as the challenges of a changing climate, including extreme weather risk, come to bear. · Political and industry advocacy:We support farmers, industry and political leaders to champion climate action in their communities and within every level of government. · Building farmer networks:We are bringing farmers together to ensure they have the strongest voice possible when calling for action on climate change. · Partnerships across industry and research: We are committed to helping the leaders of Australian agriculture become champions for climate action. Rural and regional Australia stands at a crossroads. With our clear natural advantages, a history of world-class research and innovation, and talented people, we have a once in a generation opportunity to build a future of resilience and sustainable growth. Regional Australia is responsible for about 40 per cent of the nation’s economic output and provides jobs for around one third of Australia’s workforce. It is the backbone of Australian agriculture, which seeks to grow from a value of around $60 billion to $100 billion over the next decade. But with climate change challenging our food producers, we have to think creatively and we have to act quickly. Farmers for Climate Action has developed a strategy called Regional Horizons to create new opportunities for jobs and industries, while building a climate-smart rural and regional Australia. It promotes existing successes, networks and investments and provides policy integration and certainty, making possible private, public and community led innovation. Regional Horizons is underpinned by four areas of work:

By implementing these areas of work, the Regional Horizons strategy could help to deliver a boom in new industries, investment in climate-smart farms, a thriving landscape carbon industry, and greater farm resilience and performance. Like many farmers in Australia and around the world, I am being challenged by climate change, but I am also excited by the innovation and determination I see in the agricultural sector to make a positive difference. Climate change is a concern for food producers today, and the food producers of tomorrow. Only by acting in an ambitious and collaborative manner will we achieve the bright and resilient food secure future that we all want. Climate change is impacting Antarctica and that has global implications. Antarctica is the coldest, windiest and driest continent on Earth. It is a vast continent that has challenged explorers, captivated scientists and inspired dreamers through the centuries. It is a place of beauty and mystery, covered with ice kilometres deep and home to some of the world’s most incredible creatures – orcas, sealions, penguins and whales to name a few.

Antarctica is also one of the regions of the world where the impacts of climate change are most apparent and pronounced. Temperatures here are rising double the rate of the global average. As oceans and air temperatures become warmer, the ice-covered land melts.This is raising sea levels, and 1m sea level rise displaces 100 million people.With huge global population numbers living along coastlines or in low lying inland regions, rising sea levels poses serious risk to people and ecosystems. Phytoplankton – the underrecognized microscopic lungs of the earth that live underneath sea-ice – take up 50% of the CO2 we produce, and give us half the oxygen we breath. Small changes in Antarctica have big changes to the rest of the planet. Antarctica is sometimes referred to as the thermostat of the world. Atmospheric and ocean temperatures are determined by what goes on at the bottom of the globe. Weather systems experienced in Australia are driven by the global circulation systems. Rainfall and temperatures over Australian farmland for instance, are interlinked by the conditions and changes in the southern white wilderness. It is this concern of rapidly changing conditions on her family’s outback sheep station that took Anika Molesworth from Australia’s arid inland to Antarctica. The climate crisis is of global proportions and is impacting the most remote corners of the globe. The drought ravaged land of far western NSW is suffering in >40oC temperatures and frequent dust-storms. The projections for Anika’s home are dire – by the time Anika is the average age on an Australian farmer her family’s sheep operation will have ceased to operate – the increase in temperature and reduced rainfall will have changed this fragile region irreversibly. Anika went to Antarcticaas part of a 12-month program with a cohort 100 women in STEMM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine) fighting for the sustainability of our planet.She will use her new knowledge and networks to develop her strategic and communication capabilities in order to influence policy and decision-making on climate action. Amplifying the voice of farmers who are grappling with the harsh realities of climate change today is a passion of hers. Anika is particularly interested in highlighting the issues of climate justice and intergenerational equity of the next generation of food producers around the world. For her, climate change is personal. Australian farmers are incredibly vulnerable to climate change, and the effects are already being felt on communities across the country. Extreme weather events, such as droughts, floods and heatwaves are reducing the productive capabilities of our country’s food and fibre producers which has a far-reaching ripple effect on rural mental health and social cohesion. Despite the heart-retching impacts already being experienced, Anika is convinced that that greatest challenge our world has ever faced can be addressed with leadership and collective action. As someone who has worked to understand the global through to local implications of climate change she knows a vibrant and productive farming future is possible – if climate change is tackled in line with what the science recommends. That means putting in place policies and strategies to reduced GHG emissions, transition Australia’s energy productions from fossil fuels to renewables, and implement carbon capture and storage solutions. Antarctica is the largest wilderness on Earth. Its glaring white mountains are epic. Its seas are teeming with life. It has a breathtaking presence with moods that shift between calmness and nature’s raw-power. You can’t help but feel insignificant here.

Despite silently lying at the end of the earth, Antarctica is changing – and it is because of us. Human impacts on oceans and cryosphere – the planet’s snow and ice – are significant and growing. The rapid melting underway in Antarctica will have far-reaching impacts on biodiversity, commercial fisheries and global climate regulation. Increased greenhouse gas emissions, from burning fossil fuels in places such as Australia, have altered large-scale oceanic and atmospheric processes and accelerated ice loss around the continent. Antarctica is one of the regions of the world where the impacts of climate change are most apparent and pronounced. Temperatures here are rising double the rate of the global average. Sea ice is the key to the Antarctic marine ecosystem, but due to rising global temperatures, it’s being impacted at an alarming rate. Antarctic krill, the keystone species in the Antarctic food web, is contracting southward on the Antarctic Peninsula as sea ice disappears due to warming ocean temperatures. Many species are dependent on krill. Whales, penguins and seals are being impacted already and are at risk of declining as critical habitats and food sources are lost. Although the challenges of protecting this incredible frozen landscape are great – there is hope. We can create networks of ocean sanctuaries around Antarctica. By establishing Marine Protection Areas (MPAs), large regions of ocean in our last wild places can provide nature space to adapt. The International Panel on Climate Change has recommended that there needs to be an increased number and size of MPAs in order to provide resilience to climate change. Currently, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Living Marine Resources (CCAMLR) has proposals on the table for the creation of three MPAs—in East Antarctica (originally proposed in 2011), the Weddell Sea, and the Antarctic Peninsula. Each would safeguard critical foraging and nursery grounds for Southern Ocean species, including seals, whales, and penguins, and preserve the region’s essential function as a carbon sink. We need to protect the largest wilderness on Earth today by acting boldly, collaboratively and with a positive legacy mindset. By Anika Molesworth

If you’re concerned about climate change, then you have to help drive change. Because time is no longer on our side. All too often we think, I can’t do it. I don’t know enough. I’ll get difficult questions from friends. I can’t influence the right people. Now’s not the right time. We fill our heads with excuses about why we as individuals can sit this one out. That there’s someone else who will do it for us. Unfortunately, I don’t believe that’s true. No one can do the work that you can do or influence in the way you can influence. And no one is going to save the world for us if we as individuals don’t make the effort to save it ourselves. So here are ways that you can drive change. Use your consumer influence:

Use your political influence:

Use your social influence:

Use your household influence:

Use your community influence:

Every person can help make their household, workplace, school, local council, or industry sector better for the planet. And if everyone decided to help drive change, just image what we could achieve! By Anika Molesworth

To my dear friend, I hope this letter finds you well. I know you are weary, and I’m not surprised. You have started your days early and finished late. You have sat out on things that you would have much rather have been doing in order to get the work done. It is no surprise you are tired. Even though you feel drained of energy and perhaps confused with the world, I want to tell you something important. You did it. You have made progress beyond your wildest imagination. And I want to thank you for that. Even though you might not see it all just yet, the changes you have made are extraordinary. You not only have changed yourself, your family and friends, your colleagues and neighbours, you have changed the world. We who work on the climate issue tend to naturally look at the big picture. We see clearly planet Earth in our minds-eye. That beautiful blue orb with swirls of green and white. We understand the links between people, landscapes, oceans, plants, animals, rainfall, temperature and climate. And when we talk about change, we are talking about big change, planet-scale change, and that’s where we set our ambition and mark our achievements. But I want you to look a bit closer to home. Zoom in even more than that. Right to where you are standing at this very moment. Now look beside you. I am standing right there next to you. I am standing right at your side. Shoulder to shoulder, holding your hand. Now look to your other side. There you find another person, standing at your shoulder, holding your other hand. And next to each of our sides is someone else. Shoulder next to shoulder next to shoulder for as long as you can see. A line of people with no end, holding hands and looking forward. Someone is holding both of mine and both of yours, and these people have been inspired by us, look up to us, believe in us, and back us. When you thought your voice wasn’t heard. It was. When you thought your message wasn’t seen. It was. When you worried that your energy was draining, your strength in the fight was weakening, and that you were left standing alone. You weren’t. You are a champion for so many. People who respect your voice and seek out what you are saying. People who believe your truth and act in a way they think you would act. People who share your message and in turn amplify your impact. You see, you were never doing this alone. We were by your side the whole time, and others were beside ours. And have you stopped to check the difference you have made? My gosh, it is admirable! Remember when you found the courage to have one of those difficult conversations with someone who didn’t see eye-to-eye with you, and perhaps you didn’t convert them, but the person who was silently listening in most definitely was. And maybe channelling your strength, they will decide to engage in one of those difficult conversations too one day. Have you noticed your recycling in the home has improved because your kids understand how important it is, the same bright faces that run out into the garden to check if the carrots in the veggie patch are ready for plucking from the rich soil and compost they made. Have you noticed how your co-worker is googling electric cars, the same co-worker who proudly told you that they had a great conversation with a producer at the local farmers market. Your neighbour has a new rainwater tank because they saw the one in your garden, and solar panels are basking in the sun on roofs up and down your street. Have you noticed the ‘Stop Adani’ red diamond signs everywhere these days, and how people can tell you what that stands for because people like you have made it a symbol of our time. Have we really moved in the right direction you ask? Of course we have! No longer do I hear sentences with “climate debate”, “climate believers” or “climate sceptics.” We have moved past that. Climate change and the environment have become the most important topics in our country, and our politicians no longer debate the science but debate who has the best policy. No longer are we asked “so what are the impacts of climate change” without the follow up “well, what do we need to do about it?” Because of people like you, awareness of the issues has improved immeasurably and the conversation has changed. And because we are now having the right conversation, we can now make meaningful action. We have engagement on this issue like never before. Students in the street are following your lead. The media outlets are now sharing your message. More people are listening than ever before, so now is not the time to let your voice falter. So what now you ask? Well I’m glad your curiosity is coming back. What now? You take a deep breath, fill out your chest, squeeze my hand tight, and we take another step forward, along with everyone else who stands at our side. We spread our optimism and paint our vision for the future more brightly and vividly than ever before. No alternative future comes close in comparison to that future we see and we share, and that is how we continue to move in the right direction. A future for our country with ambitious and science-based climate and energy policies, national climate adaptation strategies for agriculture, electric vehicles powered by renewable energy that we generate, so much renewable energy in fact that we export it overseas! We paint a future of healthy natural landscapes that are full of life because we used our wisdom to plant trees, revegetate the countryside, and protect the ancient giants who stand in our forests and along our riverbanks. Our vision of using our skills and incredible technology that we have in the Lucky Country to capture carbon, design the most energy-efficient houses with recycled materials, use the best crop and livestock genetics so we are resilient and bring down CO2 levels. And we encourage others to be creative and use their imaginations to come up with even more solutions! We know how urgent the need for addressing climate change is. We know how critical the situation is. We know there are big steps to be taken, but we’ve got this. And if you happen to glance back over your shoulder, you will see just how far we have come. But now, let’s look forward, and create that future that we will all be proud of. By Anika Molesworth

Please, whatever you feel, don’t let it be sympathy for me. In response to the recent interest to the video I posted of a dust-storm sweeping across my family’s farm whilst I was out doing an evening water-run, I thought I should make something clear. Watch the video. Understand what is currently occurring in far western New South Wales. Let emotions swell – but please don’t let those emotions be of sympathy for me. I am truly blessed to working in the agricultural sector. There is not a day that goes by that I would rather be doing anything else. It is without doubt, one of the most vibrant, dynamic, meaningful industries that I can think of. I wake up in the morning to the chattering of guinea fowl outside my bedroom window and corellas perched in swaying gumtrees. My horses whinny for me to feed them before I have my own breakfast, and by mid-morning I’m usually bumping along a track with my mum to go check the fences or clean out a sheep trough. During the heat of the day I am indoors at my computer writing up my PhD thesis – on how to recycle and revalue agricultural by-products to improve soil fertility and capture nutrients within local farming systems. In the afternoons I often have teleconferences, where I connect with people around the country – my university supervisors at the Centre for Regional and Rural Futures, the Farmers for Climate Action group, or the incredible Youth Voices Leadership Team. These conversations are focused on harnessing the energy that lives in this sector, how to share the enthusiasm that people in agriculture feel for their homes, crops and livestock, and how to ensure vibrancy and resiliency for all rural and regional Australia. At sunset I walk our dogs down to the dam, where they run, bark and splash in the evening light. We often take binoculars to the water’s edge to check out the birdlife – these last few weeks we’ve spotted white-faced herons, rainbow bee-eaters and black-fronted dotterels. Kangaroos nonchalantly hop down for a drink amongst the evening’s goings-on, and swallows skim the water’s surface for insects as the sun dips below the horizon. Rural Australia is a place you can easily fall in love with. She is beautiful and calming. She is also extremely fragile. My love for this place is why when I see her in pain, I feel that pain. I feel incredibly frustrated that I cannot do more to help her. I experience the drought, heatwaves and dust-storms with her and I see the toll it takes on the place I call home. I become angry. I become so angry that we’ve known for over 5 decades that certain actions lead to certain impacts – and yet we have allowed these actions to continue. Despite the science unequivocally telling us that humans are driving changes in our climate systems – that this alters temperatures on land and in oceans, that this disrupts rainfall patterns and exacerbates extreme weather events – we have continued in a national “she’ll be right” manner. I am angry that some of the people in Australian politics – who have the capacity to push for the changes needed at a national scale – instead promote coal-fired power stations and show a deep-seated reluctance to acknowledge that carbon emissions must be curtailed. I am one of the many people in Australian agriculture who is angry and disappointed by the woeful inaction on climate change and blatant disregard for the science. There is an outcry from the farming community across Australia that ‘business as usual’ is no longer an option. That words and no action give us no relief, and what we need are ambitious climate and energy strategies to be put in place urgently. I don’t want sympathy. I want you to get as angry as I am. Angry at the situation and motivated to see it change. Angry enough to stand-up, speak-out and demand that climate inaction will not continue on our watch. Because combating our greatest challenges requires all of us to contribute unique skills and knowledge to the solutions, and together, using determined minds and hearts, the best available science and conversation, we can change this. By Anika Molesworth

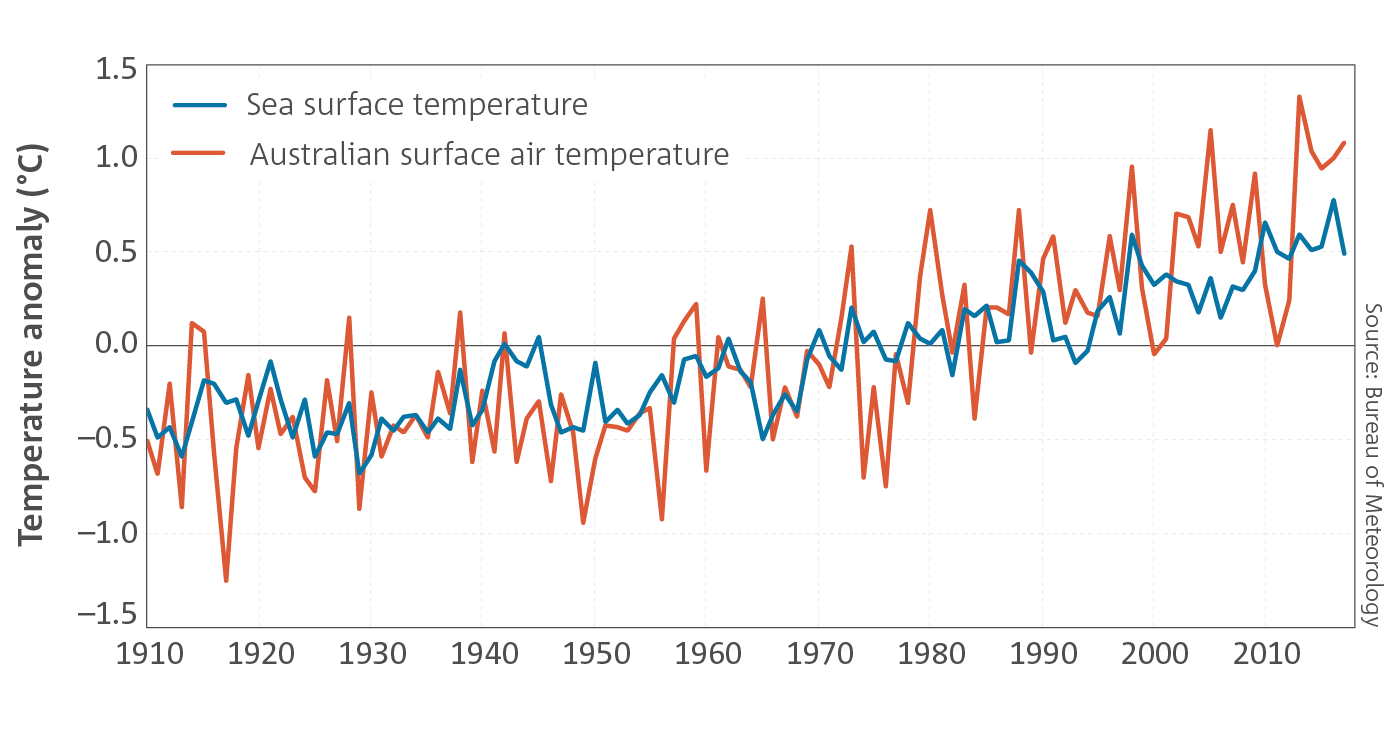

This fifth, biennial State of the Climate report draws on the latest monitoring, science and projection information to describe variability and changes in Australia’s climate. The observations and climate modelling paint a consistent picture with numerous other reports and recent data – of ongoing, long term climate change interacting with underlying natural variability. This latest document, compiled by CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology, sits alongside recent scientific warnings presented in the IPCC Special Report, UN 2018 Emissions Gap Report, the National GHG inventory, the Climate Change Performance Index and many others – which say, in a nutshell, things aren’t looking great and we’re a long way off from meeting Australia’s climate commitments “in a canter”. Perhaps it’s the two-weeks of +40oC temperatures I’ve experienced this summer which have me feeling a little hot under the collar about all this. I’ve had an attack of heatstroke, stressed over the stress I can see on our livestock, dragged away collapsed animals from dams and troughs, carried buckets of water to our trees growing around our shearing shed in the desperate attempt to keep them going, watched media headlines of a million fish dying of toxic algae blooms in our closest river, swept out our house of red sand after another dust-storm… and what’s the current weather report telling me? Over forties and no rain on the horizon. Climate change affects all aspects of Australian life – but hits rural Australia and the agricultural sector pretty hard. This is due to changes associated with increases in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, like heatwaves, bushfire and drought. Across the Murray-Darling Basin, stream flows have declined by 41% since the mid-1990s. That has huge implications for the availability and cost of water for farmers and the proper ecological functioning of these precious life-giving systems. I get that “the only solution is rain” (Canberra’s broken-record stuck on repeat) but to follow on by saying "and we have no control over that" is factually incorrect. We are unequivocally changing the planets climate system. This is what the science has been telling us for the last 50 years! I would honestly feel a little more comfortable about this hot and sticky situation, knowing that we were understanding the magnitude of what is being presented in the science, heed the urgency for action required, learn from the current devastation of drought sweeping the country, and put in place ambitious climate and energy policies. Not tomorrow. Not after the next ecological disaster or mass fish die-off. But right now! We know that a healthy environment and a healthy climate is essential for everything this is supported by it – our communities, our businesses, and for the protection of those places we love and call home. Australia needs to plan for and adapt to climate change. We need to reduce the unspeakably harmful pollution we are pumping into our skies like it’s an open sewer, and refuse new coal mines from being built. Many of the solutions already exist and are ready to be implemented – but we need strong political leadership on this issue. Politicians who claim to represent rural Australia must push for policies that actually ensure the resilience and sustainability of our regions in the face of climate change. By Anika Molesworth

The images of dust storms across Far West NSW have spurred me to write this article. If you’ve ever stood before an approaching dust storm, you will know what I mean when I describe it as a formidable dark beast crawling along the landscape. Bellowing a low grumble as it makes its way across vast stretches within minutes, unfolding to the heavens and engulfing everything in its way. It’s a sight we out west have seen numerous times during this drought. A powerful reminder of one’s insignificance in the face of Mother Nature – and simultaneously our impact upon her. But dust storms are not new to this region. Broken Hill township was established in 1883, and by the early 1900s overgrazing and mining operations had denuded the landscape. Sand drifts and dust storms threated the town, and rags were regularly jammed under doorways and along window seals to prevent red dust creeping into one’s house. Images of this time period remind us of how bad it got. And how, in the face of such adversity, locals banded together to fight for their future. Led by Albert and Margaret Morris and William MacGillivray, the Barrier Field Naturalists club was established and one of the earliest known ecological regeneration projects in the world began. The vision for a set of regeneration reserves started in the early 1920s, and by 1936 the first had been established. The benefits of the reserves in reducing dust became clear to the townspeople, and the scheme was soon being championed by locals and community groups. More than 80 years since the first reserve was established the benefits of the regeneration reserves to wildlife, vegetation and the town are still clear. Take a stroll through the natural green belt that wraps around the Silver City, and see the striking red flashes of Sturt Desert Pea and the bedeared dragons lounging on Ruby Saltbush. But despite a harsh exterior, we are reminded that this landscape is incredibly fragile. The recent dust storms highlight just how vulnerable these special places are if we do not look after our common home. In a region that is projected to become hotter, drier and experience more frequent and intense droughts and dust storms, what does the future hold for towns like Broken Hill in semi-arid inland Australia? Our future rests in our hands. Just like the courageous people who defiantly changed the trajectory before, so again the outback people stand with their home and fight for its future. Whether it’s to save the Darling River, the Menindee Lake system, endangered wildlife or farming families, the power and might of dust storms rolling across the landscape remind me of the groundswell happening in these rural communities. Outback people have resilience and fight imprinted in their DNA. Our climate and environment are changing rapidly and we will not sit quietly and accept inaction. Hear the rumble, cause we’re fighting for our future. By Anika Molesworth

In failing to act on human-induced climate change, our political leaders are neglecting the rights of the next generation. You just need to turn on your television to know this drought is tough. Every evening, Australian families are being bombarded with footage of struggling farmers, dust-bowl paddocks and hungry animals. The bad news is that the extreme weather events plaguing Australian agriculture are about to get worse. This drought is not an anomaly. It’s not a once-in-one hundred year event. It’s inextricably linked to human-induced climate change. We’ve known for more than 50 years that the carbon dioxide produced by burning fossil fuels is destabilising the climate system. Right now, that’s set to continue with the IPCC Fifth Assessment report warning that ‘continued emission of greenhouse gases will cause further warming and long-lasting changes in all components of the climate system, increasing the likelihood of severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts for people and ecosystems.’ Despite all of this evidence, our political leaders have continued to campaign for new coal mines. They have failed to develop a clear and ambitious strategy to transition to renewable energy. Even now, in the depths of the worst drought of our generation, no political leaders are openly discussing what is needed to arrest climate change impacts. This failure to act in regards to human-induced climate change is fundamentally an issue of intergenerational justice. Our leaders have been aware of the hard-scientific evidence of climate change for decades, yet they have failed to act. In so doing, the benefits of present generations have been put ahead of the rights of the next. As a young person with the dream of taking on the family sheep property, I am being unfairly disadvantaged by this failure to take action. My family’s sheep farm in far west New South Wales is projected to become hotter and drier, with more frequent and intense dust storms due to human-induced climate change. High temperatures can stress our livestock, reduce fertility, increase mortality and adversely affect pasture and fodder crops. In the near future (2020–2039), this region could expect maximum temperature increases of 1oC. In the longer term (2060–2079), this could rise to 2.7oC. The viability of our farming operation – and my future as the custodian of this property – is precarious. The hurdles facing the next generation of food and fibre producers are great. There’s no denying it. The combined challenges of feeding a growing number of people on the planet, with reduced environmental footprint, on a backdrop of social pressures and climate change, will ask more of these farmers than ever before. Building the support structures now in policy and institutions that are forward-thinking, ambitious and embrace intergenerational equity is essential. As a young farmer, I am calling on our government to do more to prevent harmful climate change impacts. The failure to protect the future of young farmers by slow or inadequate action violates their rights to life, liberty and property enjoyed by previous generations. The idleness in setting in place policies and structures to reduce pollution emissions exacerbates the risk and intensity of droughts, pest-outbreaks and floods – threatening those setting out on a career in agriculture. Climate change is impacting me personally. My future is being re-written. Extreme high summer temperatures will make my working conditions less safe, it will reduce the profitability of my farm through diminished livestock capacity, and this will have flow-on effect to the vitality of my rural community. Our government is accountable for taking action to fight climate change. The alleged danger of drought has been sufficiently demonstrated – we see that on the faces of the farmers pushed to the edge on the nightly news – and there is direct link connecting CO2emissions to the danger of drought. Ignoring these facts is putting people’s futures at risk. Farmers are people who generally have their eyes on the horizon, from planning the next growing season to ensuring a strong working farm for their kids in their succession plan. As landmanagers we know we have responsibilities to the next generation so we also must be part of the story in reducing greenhouse gases arising from agriculture and taking care of the places we call home. And as a wider society, we have certain obligations to the welfare of future generations. This obligation to future generations must guide the strategies that we adopt to address issues like climate change, to minimise damage caused by changes already set in place, and ensure that young people receive the tools and resources to help them adapt. Many of the solutions already exist, from renewable energy technologies that reduce pollution, to education programs on best-practices in a changed climate – what we need urgently is now the political will to change our current trajectory in the magnitude necessary for the better. Climate justice means implementing measures that effectively protect young citizens from the foreseeable impacts of climate change – and that means taking ambitious action today. By Anika Molesworth

I have an uneasy queasy feeling. The kind one gets after being on rough waters too long. A dull nausea feeling in my gut and a lump in my throat. I am feeling a sense of agitation, yet I stopped drinking coffee months ago. Each day images of drought affected Australia fill my newsfeed. Emaciated livestock, barren paddocks and stoic farmers breaking down on camera. As I write this, a dust storm is howling outside and I’ve brought the dog indoors so he isn’t coughing on the desiccated topsoil whipping through my yard. I’ve just finished an interview with breakfast radio, and have another interview after lunch. Everyone seems to have discovered the drought this week. A “hot topic” that will once again blow away when the attention span wavers. Interview questions come from the same handbook – with an unoriginal sentence structure incorporating ‘debate’ and ‘belief’ on ‘climate change’. The unambitious NEG also raising its head. Its salt in the wound for farmers in the middle of the drought. Like having a terminally ill family member, then being asked if you ‘believe’ the best available science on its cause, and perhaps we should ‘debate’ the illness itself. In the meantime, why don’t we offer a ‘remedy’ that won’t do much at all. Doesn’t that sound good? Sometimes I feel it’s easier to tune-out than tune-in. To turn off the newsfeed and stop answering the journalist’s calls. The answer to the question “are you concerned about your farming future” is yes. The answer to the question “are you worried about the increased frequency and intensity of droughts projected” is yes. And the more I think about these things the more the queasy feeling grows. But I won’t tune-out when the newsfeed grows more raw. And I won’t tune-out when the “hot topic” of the week changes and the images of drought dry up as quickly as our dams. There is too much at stake. Farmers around the country demand that climate change is addressed with urgent and ambitious action. Business as usual is no longer an option. Ending Australia’s reliance on fossil fuels is the easiest and most economically sensible way to reduce pollution. I ask that each person who is as heartbroken by the images of drought affected Australia as I am, to tune-in, step-up and speak loudly that now is the time to put in place the strategies to reduce emissions in line with what the experts recommend. Our future depends upon it. |